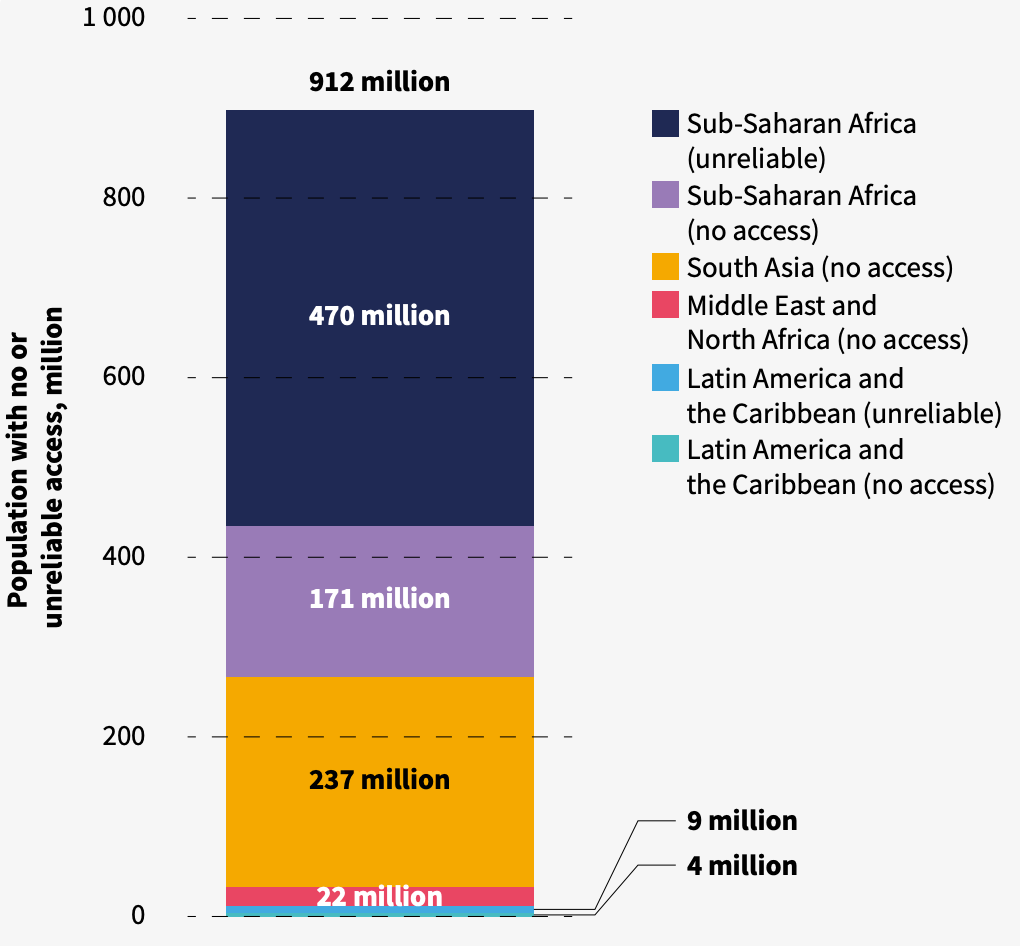

Nearly one billion people in low- and middle-income countries lack access to health facilities with reliable electricity, a joint report by the World Health Organization (WHO), World Bank, and International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) found.

Electricity is essential for the functioning of medical equipment like ventilators, incubators, and cold-chain storage for vaccines, as well as basic hospital needs like computers and air circulation systems required to keep them running smoothly. Without a steady supply of electricity, healthcare services like childbirth, emergency care, and vaccinations cannot be adequately provided.

Yet despite its importance, the electrification of healthcare infrastructure has long been overlooked, leaving one-eight of the global population in danger of not being able to reliably access the care they need. In total, over 430 million people are served by medical facilities without any electricity at all.

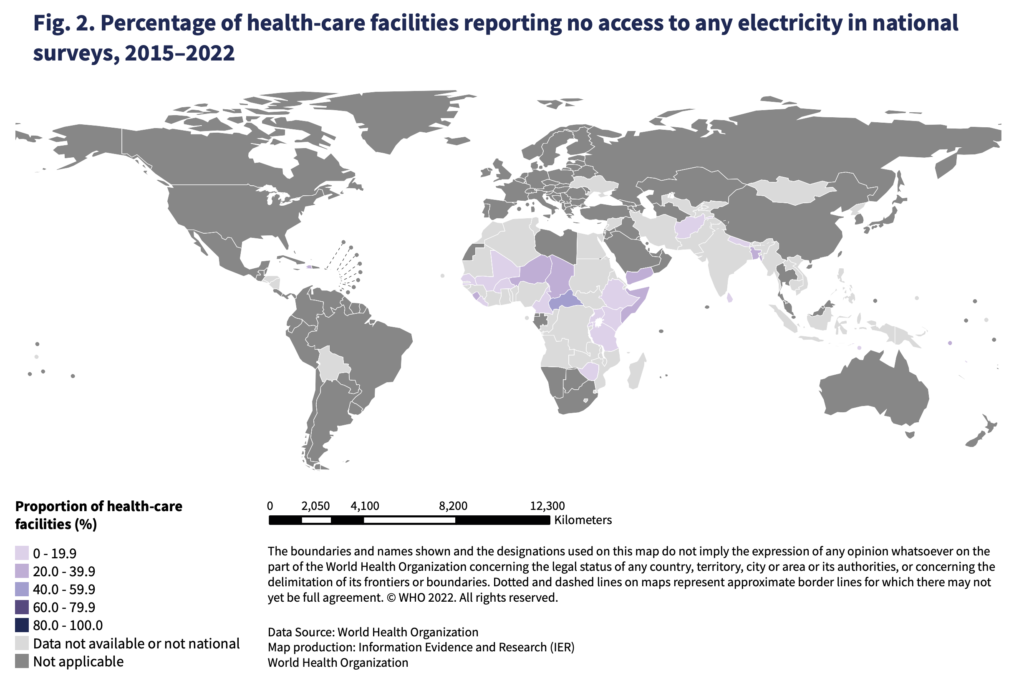

The report is the first to map electricity access in low- and middle-income countries worldwide, and revealed large gaps in electricity access in the world’s poorest countries. In South Asia and Sub-Saharan countries, only half of health facilities reported having reliable access to electricity, while 12-15%, or 25,000 facilities, reported having no electricity whatsoever.

“It is simply unacceptable that tens of thousands of clinics in rural areas of Asia, Africa, and Latin America are equipped with little more than kerosene lanterns and rapid diagnostic tests,” the report said. “The image of health care providers bent over a patient’s bedside, hand-holding his or her pulse under a fading kerosene lamp – needs to be relegated once and for all to the annals of history.”

$4.9 billion to bring facilities up to a minimal standard

At least 912 million people across Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and sub-Saharan Africa rely on medical facilities with no electricity access or an unreliable energy supply. An analysis by the World Bank included in the report found that nearly two-thirds of facilities across these regions are in need of urgent intervention to improve their access to reliable electricity.

With over 100,000 facilities requiring new off-grid electrical connections and over 230,000 others needing a backup energy system, the World Bank estimates $4.9 billion will be required to bring them to a minimal standard of electrification.

But the cost-estimate limits itself only to the most basic level of energy needs required to operate essential health services, set at 15 kilowatts per hour for non-hospitals such as clinics and 500 kilowatts per hour for hospitals, and does not reflect the same standard present in hospitals in rich countries.

But increasing non-hospitals energy access to 32 kilowatts per hour, which would allow for the provision of a broader range of healthcare services, increases the price tag to $8.9 billion.

Importantly, the estimates also do not include costs related to the acquisition of new medical equipment. Electrification without a parallel investment in such equipment, the report found, would be an incomplete strategy, meaning the real amount of investment needed is higher than the figures set forth in the report.

“This required amount is much lower than the social cost of inaction,” the report said.

No need to “wait for the grid”

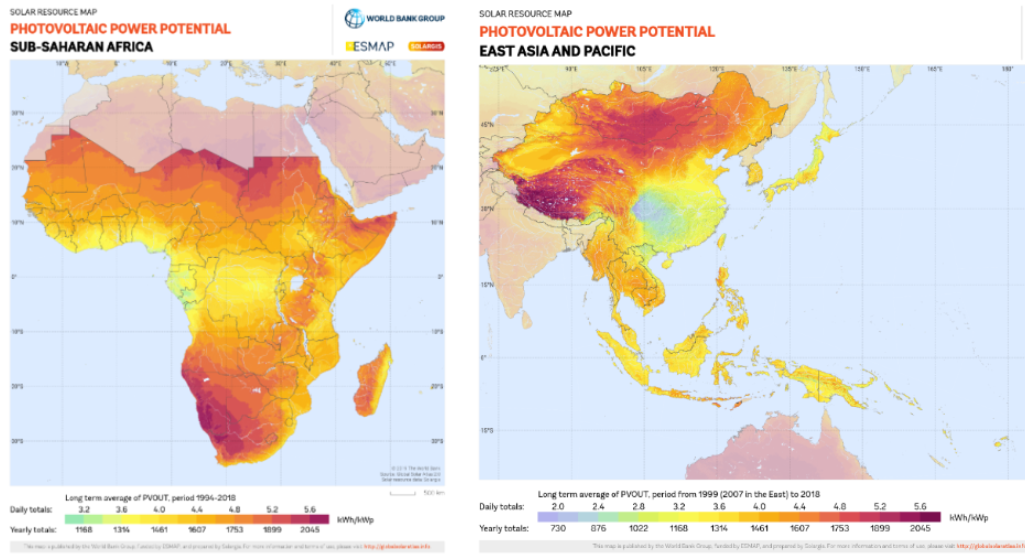

Sub-Saharan Africa and East and Pacific Asia, the two regions with the highest rates of non-electrified health facilities, are ideally situated to take advantage of advances in solar technology.

Centralised grid extension has long served as the go-to strategy for expanding energy access. But this approach often falls short when trying to reach rural and remote regions of low-income countries due to the distance the grid needs to expand to reach the populations living in their farthest reaches.

Technological advances and price drops in renewables, especially solar, have triggered a rethink of the grid-based approach. Instead, the report found decentralized sustainable energy solutions are often “the most technically and economically viable solution” to reach people living in areas with challenging terrain for traditional infrastructural expansion.

In a presentation delivered at the report’s launch event, Dr Maria Neira, acting assistant-director general of Healthier Populations at the WHO, said there are “no excuses” for not making progress on increasing access to decentralized, sustainable energy sources given the availability and affordability of these technologies.

“No need to wait for the grid. IRENA has pointed out the role of centralized renewable energy to increase electricity access,” she said. “It’s cheap and more resilient to climate change. This is a major development priority as it saves lives.”

Decentralized approaches have the added benefit of allowing healthcare facilities to be energy independent, insulating them from the risks of fuel shortages or price shocks inherent to a reliance on fuel generators. The higher reliability of renewable energy solutions, in turn, means higher uptime for life saving medical equipment, and essentials like clean water access, particularly in regions vulnerable to water insecurity or extreme weather events.

“Solutions are available and rapidly deployable,” the report added. “The impact on saving lives and improving the health of vulnerable populations would be huge.”

Electricity access is a story of inequalities

Stark inequalities in accessing reliable electricity in healthcare facilities emerge when comparing different countries based on income, facility type, and location.

Generally, facilities in low-income countries have less access to reliable electricity than those in lower-middle-income countries. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia have the lowest rates of electrification, followed by the Pacific and East Asia regions.

Low rates of medical facility electrification are often symptoms of a wider lack of development of energy infrastructure. In South Sudan, for example, overall energy access – let alone that for medical facilities – was estimated at just 7.24% nationally.

Disparities in access to electricity are also pronounced within countries. Non-hospital healthcare facilities, like primary health centers, which often serve poorer regions due to their lower operating costs, tend to have less access to reliable electricity supplies than hospitals. A divide can also be seen between urban and rural areas, with urban healthcare facilities reporting better access to than rural facilities in the same country.

Until the electrification gap can be bridged, one eighth of the world’s population, equal to the populations of the United States, Pakistan, Indonesia and Germany combined, remain in a medical no man’s land.

“Electricity access in healthcare facilities can make the difference between life and death,” Neira said.

Image Credits: WHO, World Bank.