The diffusion of innovation theory, first described by Everett Rogers in 1962, focuses on how new, innovative products spread in markets. Typically, these new products—whether iPhones, mini steel mills, or the latest cool trainers (or sneakers for our American friends)—are first bought by a group of innovators and early adopters. These people have a high-risk appetite and they want to be the first to have “the next new thing.” These customers test out new products or services and, for ones they like, use their outsized influence and social capital to spread word of that product through their networks.

This theory is well-developed and studied in mature markets. And though it has also been applied conceptually to social businesses and public-sector interventions in the developing world (e.g. Monu, African Studies Review, 1982), there has been little systematic customer-level insight into whether Rogers’ model accurately describes the adoption of new innovations for more marginalised, lower-income customers. This research gap is important: understanding and managing the diffusion curve and routes to market can help entrepreneurs and their teams turn new, niche innovations into mass market products—but this only makes sense if the theory accurately describes reality in these settings.

Our team at 60 Decibels set out to study this question through a number of Lean DataSM projects in 2019. 60 Decibels is a customer-focused impact measurement firm that recently spun out of Acumen (see this June 2019 NextBillion article for more details). Our Lean Data approach turns customer voice into high-value insights that help businesses maximise their impact.

Recently, we set out to understand the adoption persona of customers served by social businesses, starting in the off-grid energy sector. Many of these enterprises are working on the front lines of innovation in developing or emerging economies, often seeking to serve last mile customers and/or low-income families with limited access to information, products and services. Understanding the true profile of early adopters – as we did in this study – is a first step towards gaining a better ground-up understanding of diffusion cycles in these new frontier markets, so that innovations can scale more rapidly and we can accelerate the rate at which critical goods and services reach those who need them most.

We asked customers to describe their attitudes and behaviours towards new products or services to determine who were early innovators, early adopters or tech laggards. In interviews with 4,400+ customers in the energy sector – 75% of respondents were solar home system customers, and the remainder had purchased solar lanterns, solar refrigerators, solar water pumps, were connected to a mini-grid, or had an improved cookstove. These 2018 interviews were part of Lean Data projects in Kenya, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia.

As in all of 60 Decibels’ Lean Data projects, we thought carefully about the flow of the interviews, the question order, and mix of qualitative and quantitative questions so that our 60 Decibels Researchers could build rapport and trust with respondents. With this in mind, we placed the adoption persona question after questions about who in the household first heard about the product/service; how and where they first heard; and who made the decision in the household to purchase the product/service. Side note; all of our 150+ researchers are locals of the countries we work in and conduct interviews with customers in their local language.

What we’ve learned so far

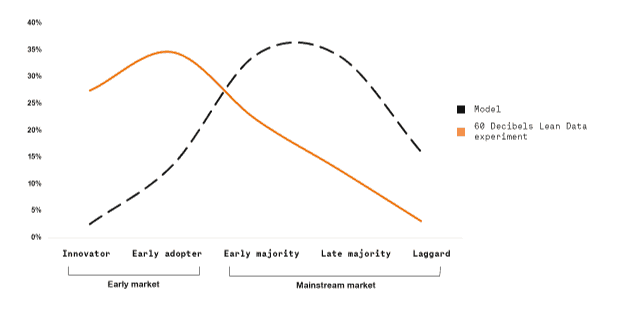

The off-grid energy sector is relatively new, and the 13 companies whose customers we interviewed have typically been in business for 10 years or less—with some much newer. Since both the companies and the sector are relatively new, we would expect that the bulk of customers will be Innovators and Early Adopters as described by the model. The results did suggest that the companies included in this experiment are serving an earlier market segment than the model (see chart).

Education level shapes uptake

Education was a key factor: Customers self-identifying within the Early Majority, Late Majority and Laggards groups were much less likely to have tertiary educations than Innovators and Early Adopters. Some 65% of the Early Market had someone in their household educated to tertiary level, compared to just 20% for Early Majority customers, 12% for Late Majority customers and 3% for Laggards.

Age and income level don’t seem to be predictors

We also saw some divergence from the predictions of the model. We expected that Innovators and Early Adopters would be younger and wealthier than other customer segments, but our data doesn’t match this prediction. The average age of all companies’ customers were 38 to 40, whereas the median age in the countries where we conducted the study ranged from 15 to 19 – although they may not be customers at this age which likely shapes results. In terms of poverty profile, 35% of the Early Market lived below the international World Bank relative poverty line at $3.20 per person per day compared to 37% of Late Market customers. We conclude that markets for critical goods and services – like access to energy – will have different dynamics than typical innovations in developed markets. These products are necessities rather than luxuries, whose purchase may be more strongly affected by income level and affordability. That means lower-income families may be more likely to take a risk, or adopt earlier, and to spend more on a necessity than a luxury item where there are other economic or well-being benefits for the whole household.

Country context is key

Country context is critical for understanding a market; we saw more correlation at a country level suggesting that these results can be better predictors with this filter.

When looking at Kenya, for example, the results show that as we look at newer, more expensive, more complex products, we see higher proportions of Innovators, better educated, and older customers with higher and more regular income.

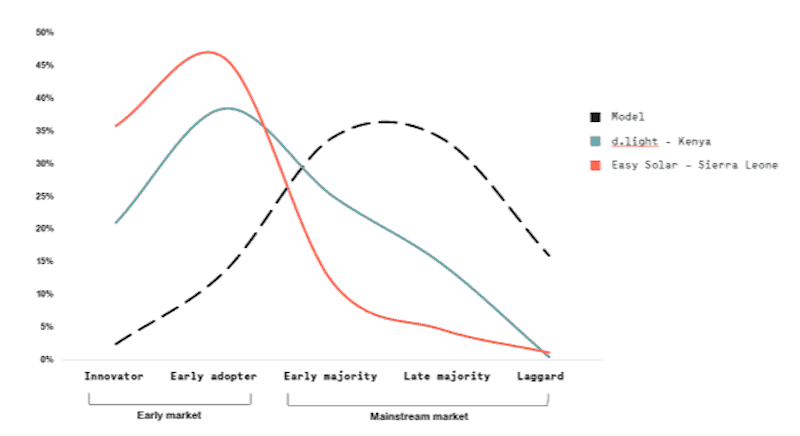

This chart compares customer adoption personas for d.light solar lanterns in Kenya (where the market is relatively mature) versus solar lanterns sold by Easy Solar in Sierra Leone (where the market is newer). In Sierra Leone, 83% of solar lantern customers are Innovators or Early Adopters, compared to 59% in Kenya.

When analysing this data, we did see evidence that Innovators tend to be wealthier than Laggards: in Kenya, 48% of Innovators in our sample live below the poverty line compared with 82% of Laggards.[1] This compared to a national poverty rate of 53% in Kenya. We saw a similar trend in Sierra Leone: 38% of Innovators live below the poverty line compared to 53% of Laggards. Interestingly, in Sierra Leone poverty profiles of Innovators and Laggards are below the national poverty rate of 73%, suggesting that in this less-developed market, solar lanterns are not yet in reach of some of the lowest income families. (Easy Solar is still expanding its distribution network to the most remote and poorest areas of the country.) We would expect that as the market grows in Sierra Leone, as Innovators and Early Adopters share their positive experience with the product, more of the less well-off may feel like it’s an investment worth making.

Next steps

So, how is this information useful?

Firstly, these results serve as a useful validation of the core thesis of the diffusion of innovation theory: new products and services, even those meeting the most basic needs like lighting and energy access, will be adopted by people who describe themselves as Innovators and Early Adopters. However, the findings about age and income point to an important difference in the markets we’ve studied: customers across the spectrum, including Innovators, were older than the population as a whole. This might reflect realities of wealth accumulation, or household roles that define older family members as the ones who make major purchase decisions for things like solar home systems.

For social enterprises, these results underline the importance of learning how to identify Innovators and Early adopters as their first customers, and how best to market to them.

Using the right words to attract your target group

One element is language; shaping marketing messages to appeal to customers we want to attract. Using words like “new”, “innovative”, or “exciting” in marketing materials and sales pitches may appeal most to the Early Market and speak to their innovative streak. A critical step is then cultivating these first movers into brand ambassadors and referral champions, as we have seen that later adopters tend to wait for trusted sources to convince them that the solution is “tried and tested”, “trusted”, or “improved” – suggesting an advantage from letting others take the risk first.

In addition, the findings on education levels of Innovators and Early Adopters versus the mainstream market might imply shifts in product marketing language over time: newer customer segments will be more highly educated and may respond better to more sophisticated language and positioning than later adopters. This sense of connection to, and identification with, the product may both attract these customers and make it more likely that they will spread the word to their friends and networks.

Positive customer experience ensures a move from early market to mainstream market

What else encourages Innovators and Early Adopters to become ambassadors? The most obvious is a consistent positive customer experience. It’s not rocket science, but it’s essential to get it right. From the tens of thousands of customers we’ve spoken to through nearly 450 Lean Data projects, here are the things we hear time and again:

- Highlight things that matter most to customers in sales pitches

- Have honest and accurate marketing

- Deliver excellent after-sales care (this one is key!)

- Resolve customer issues easily and quickly

- and show customers you care by asking for their feedback.

All of this contributes to improved repayments on financing, higher customer satisfaction, and ultimately more successful businesses that grow and scale.

While the notion of customer centricity is not new, executing on a consistent, positive customer experience while also addressing all the challenges of product development, financing, distribution and operations is never easy. It can help if companies decide which customer group(s) are most important and deliver a consistently outstanding experience to these customers first. For new technologies and businesses, this customer will likely be someone who feels comfortable taking risks on a new product, service, technology, or brand. Once these early customers are using the new product or service, they become ‘Promoters’ of the product, spreading their experience through positive word-of-mouth to the wider community.

[1] We estimated poverty levels using the Poverty Probability Index® which gives the likelihood that a given respondent, or population of respondents, lives below the local poverty line.

Kat Harrison is Director of Impact at 60 Decibels leading the Africa operations and energy work. 60 Decibels is a new social enterprise spun out of non-profit impact investor Acumen.

Hassan Nasser is an Associate at 60 Decibels and is pursuing a Masters in Public Administration at the London School of Economics.

First published at NextBillion. Republishing with permission.